Toward the end of season two of Homeland, kinda-sorta terrorist Nick Brody helps a bonafide terrorist hack the pacemaker of the U.S. vice president (who happens to be a pretty huge jerk). Brody breaks into the vice president’s place, finds the case that goes with the pacemaker and gives the bad guy the serial number. A few minutes later, Brody looks into the eyes of the vice president and, just for good measure, tells the VP that he’s killing him as the VP clutches his chest and projects hate at Brody with all the force his dilating pupils can muster.

That scene made me think of the Nebula award-winning short story by Harlan Ellison called “‘Repent, Harlequin,’ Said the Tick-Tock Man.” This is the story that the movie In Time was based on. In fact, Ellison sued for the likeness, but dropped the suit—maybe because he didn’t want his name associated with that waste of two hours. Anyway, in “Repent, Harlequin,” when someone’s time is up, the Tick-Tock man responsible for monitoring and tallying everyone’s comings and goings to shave time off the lives of those who aren’t punctual sends a signal that stops the person’s heart instantaneously. It’s almost like a pacemaker hack, except there’s no pacemaker.

I was surprised when some viewers found the Homeland scene ridiculous. I bought it without a second thought—not only could that happen, but I figured it probably already had. But being a cynic isn’t proof, so I decided to find out whether a remote pacemaker hack is possible.

The answer is yes, it’s possible, depending on the type of pacemaker, but pacemaker makers (it’s too good for a synonym) have been working to ensure that it’s pretty darn difficult.

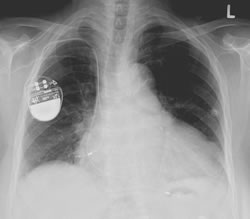

First off, pacemakers monitor one’s heart rate and if it identifies any kind of arrhythmia, it will attempt to regulate the electrical rhythm of the heart by delivering a low voltage pulse. Such a pulse couldn’t kill someone, and pacemakers aren’t capable of sending high-voltage shocks.

But some implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are. ICDs are used for patients who suffer from ventricular fibrillation, which is the most dangerous kind of arrthymia—the associated cardiac muscle contractions are a common cause of sudden cardiac death. If an ICD detects such a contraction, it will counteract that with a shock.

The VP’s pacemaker in Homeland is, from the plastic box and its accessories, identifiable as an ICD. Such a box can facilitate remote monitoring so a doctor can view data. There’s also a wand in that box, which doctors use to program ICDs and pacemakers. Before FDA approval of wireless pacemakers back in 2006, the wand had to be in close contact with the device, but nowadays there’s something called the Medical Implant Communication Service that allows for remote programming. Now, ICD devices have a programmer or transmitter that can be accessed using a serial number. Generally, though, a doctor couldn’t just dial in and reprogram the ICD on the fly—the transmitter transmits information, rather than receives it.

While uncommon, there are some models of ICDs that have enabled remote shock delivery, primarily for testing purposes (testing what, I wonder?). Depending on the specific ICD, remote delivery of 800 volt shocks to an ICD is possible. Whether such a shock would kill someone or simply cause them a great deal of pain is unclear—probably the latter, but I guess the VP’s heart was particularly diseased. More problematic for the Homeland scenario is the location of the hacker. It’s never revealed—we just see the electrocardiogram readouts on his laptop and then through his super sneaky hacker software he gets the ICD to defibrillate. The hacker would have to be nearby, though (as in, in the same building), especially because the remote monitor wasn’t connected, which…oops. That hacker was good!

The Homeland writers apparently got their inspiration from a 2008 New York Times piece about a study in which computer security researchers wirelessly accessed a defibrillator-pacemaker. The study ultimately concluded that no incidents had ever occurred and that while the F.D.A. would be closely examining such technologies and promoting added security, people with pacemakers didn’t need to worry. But not all people agree. In this TEDx talk, Avi Rubin claims that any and all devices, including voting machines, can be hacked.

And professional hacker Barnaby Jack was found dead just before he was about to deliver a presentation about hacking pacemakers, insulin pumps, and other medical devices, and to offer suggestions for enhanced security and safety measures. Wow—do you think Abu Nazir’s hacker got to him, too?

One person who didn’t believe he was safe from pacemaker hacking is Dick Cheney. I’m not totally sure whether VP Walden was intended to resemble Cheney (he didn’t shoot any of his friends in the face, but he did enjoy some deadly Middle East drone strikes), but the former VP whose defibrillator helped regulate his heart after five heart attacks was worried that the device might make him vulnerable to attack. In 2007, his doctors turned off his pacemaker’s wireless functionality for fear that someone might try to kill him. Now, Cheney has a new heart, so I guess we’re back to throwing shoes, which to my knowledge, we still can’t do remotely.