In Larry Niven’s Known Space stories, humanity has advanced to the point of producing pleasure by tinkering with the brain, rendering other vices obsolete. “Wireheads” have electronic brain implants, “drouds,” that tickle their brains’ pleasure centers. Not surprisingly, people become addicted to wireheading.

Niven was spot on. Wireheading exists almost exactly as he describes it and involves using neurotechnology, electrodes, or a brain-computer interface to stimulate the pleasure center of the brain. Certain regions of the brain, such as the mesolimbic dopamine system, trigger incentives for actions and objects that make people happy, such as food, sex, and socializing. This circuit also enables the memory to encode these happiness-inducing events, which provides motivation to repeat them later. But unlike those activities, stimulating the area directly releases a flood of virtually endless pleasure.

Essentially, wireheading equals bliss. It’s pretty simple, really. So why wouldn’t everyone wirehead?

Niven answers that question too. In his works, wireheads succumb to the same fate as drug addicts—they become single-minded and sacrifice their health in pursuit of endless bliss. In Niven’s 1969 short story “Death by Ecstasy,” a character named Gil Hamilton discovers his friend, Owen, dead. Owen died in a chair with both food and water within reach, so Hamilton figures something must have gone wrong. After a bit of searching, Hamilton discovers the cause of his friend’s death:

It was a standard surgical job. Owen could have had it done anywhere. A hole in his scalp, invisible under the hair, nearly impossible to find even if you knew what you were looking for. Even your best friends wouldn’t know, unless they caught you with the droud plugged in. But the tiny hole marked a bigger plug set in the bone of the skull. I touched the ecstasy plug with my imaginary fingertips, then ran down the hair-fine wire going deep into Owen’s brain, down into the pleasure center. No, the extra current hadn’t killed him. What had killed Owen was his lack of willpower. He had been unwilling to get up.

Wireheads, whose brains receive the pleasure-inducing current via an aptly named “ecstasy plug,” are consumed by pleasure to the extent they die from self-neglect. Niven’s 1979 novel Ringworld Engineers opens with Louis Wu “under the wire” and thus unaware of two intruders who find him “lost in the joy that only a wirehead knows” and who knew “what to expect” because “they knew they were dealing with a current addict.” Wu survives that encounter and throughout the book struggles to quit. In fact, Wu—a character who also appears in the Known Space stories—is the only recovered wirehead addict in Niven’s work, in which the practice of wireheading becomes so ubiquitous that it affects natural selection—evolution favors those endowed with willpower and self-control, and selects against those that can’t overcome their addiction to pleasure.

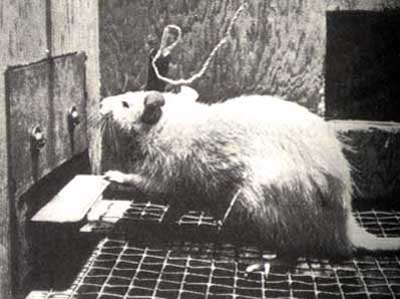

While I haven’t heard about any human wirehead addicts (although House did try to trick doctors into stimulating his brain’s pleasure center to cure his depression, so he probably would have been), rats make for a convincing cautionary tale (tail?). In 1954, psychologists James Olds and Peter Milner conducted a study in which rats could press a lever to induce pleasure via electrodes in their brains. The rats pressed this lever up to 2000 times per hour, particularly when the stimulation focused specifically on the septum and nucleus accumbens, both parts of the mesolimbic dopamine system.

Olds and Milner’s rat wireheading study was the first to identify the brain’s pleasure center and the identification of dopamine as a pleasure-inducing chemical followed soon after. Perhaps those rats inspired Niven’s work—they pressed that lever to the exclusion of other needs and many of them died of starvation and dehydration.

Some groups, including transhumanists (as represented specifically in David Pearce’s “The Hedonistic Imperative”) aim to alleviate psychological discomfort and replace it with “states of sublime well-being.” But Pearce may have read his Nivens—he admits that wireheads are “not evolutionarily stable.” He even calls wireheading a “recipe for stasis.” As tempting as it might be to induce an endless surge of pleasure, humans would have little incentive to problem-solve, cope with adversity, or change their behaviors (or do anything at all).

Stimulating the brain via an electrical current isn’t just about inducing pleasure, though. Techniques such as Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) involve implanting electrodes into the brain for impulse regulation or brain chemical alteration. Wires run from the brain to a pacemaker in the patient’s chest used to control the impulses. In cases where medication isn’t effective or has become ineffective over time, DBS can treat neurological conditions and movement disorders such as Parkinson’s, essential tremor, OCD, dystonia, epilepsy, Tourette’s, depression, and some headaches. The results of DBS can be extraordinary, as in the case of Andrew Johnson, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s at age 35.

DBS has also enabled enable minimally-conscious patients and those in vegetative statements to communicate temporarily via blinking, eye movement, nodding, and hand/finger movement.

In the Ringworld novels, Niven also writes about something called a “tasp,” a non-surgical device that enables the remote stimulation of a person’s neural pleasure center (provided the person gives consent beforehand, of course). A tasp bears resemblance to DBS, and even more closely to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), which stimulates nerve cells in the brain via an electromagnetic coil. TMS has gained traction as treatment for people who suffer depression that hasn’t responded to more conventional treatments. In Niven’s work, tasps control behavior, such as ensuring that the warlike kzin won’t cause trouble during transport. While remotely controlling someone via tasp is only supposed to happen with one’s consent, “taspers” often use the technology “on someone who isn’t expecting it. That’s where the fun comes in.”

Both DBS and TMS raise ethical questions regarding their use, especially when it comes to unknown of little known side effects and implications on patients’ identities. But there haven’t been any reports of DBS or TMS patients jolting themselves into oblivion or states of self-neglect. While studies about the efficacy of these approaches remain varied and ultimately inconclusive, some of the success stories are undeniably dramatic.

So if wireheading isn’t the solution to unhappiness, what is?

David Pearce suggests “permanent stimulation of upregulated mu opioid receptors—without dopamine-driven desire,” an approach that requires substituting something else for dopamine—in this case, opioid receptors. So this might not be the way to have the high without the crash or the jones for a fix and is likely infeasible in the long run. Ultimately, some transhumanists advocate a more invasive approach—genomic modification.

That’s right. With a little tinkering of the ol’ DNA, humans might all become hyperthymic—perpetually happy regardless of circumstances. But what fun would life be if we had nothing to complain about?

One Response to Wired for Bliss