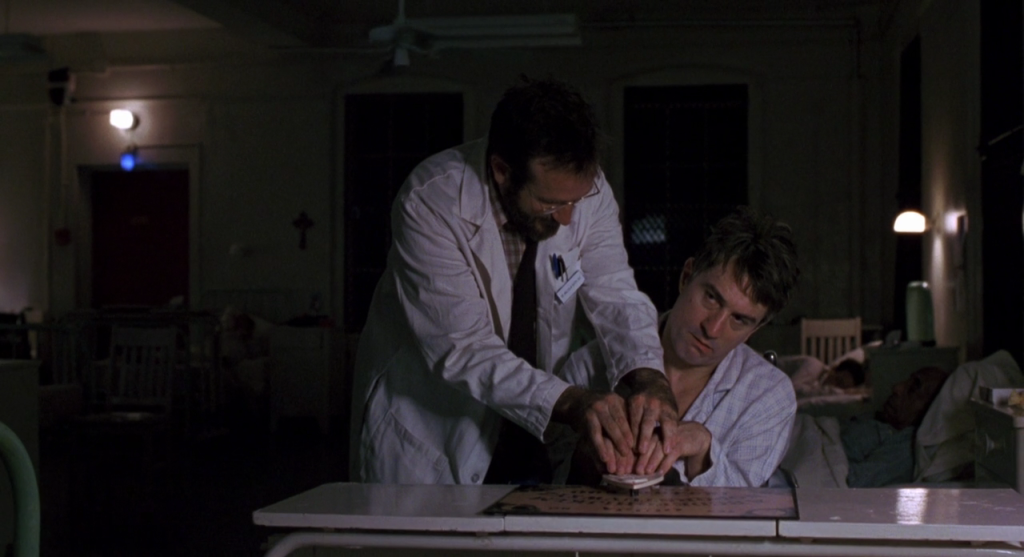

British neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote Awakenings in 1973, detailing his experiences giving a drug called L-Dopa (Levodopa, now commonly used to treat the symptoms of Parkinson’s by increasing the brain’s supply of dopamine) to catatonic patients. The book was later made into the movie Awakenings, starring Robin Williams as the doctor and Robert De Niro as one of the patients who awoke after being administered L-Dopa. Sudden awakenings from catatonic or comatose states are staples in science fiction, as writers and directors can fling unsuspecting and unconscious characters into space, as in Pandorum; give them post-awakening psychic abilities, as in Dead Zone; or suddenly awake mass numbers of comatose patients with the directive to stop World War III, as in the forthcoming Coma. Even though these sudden awakenings may seem unbelievable, Sacks’ L-Dopa treatments really were that effective—at least for a while. They allowed patients to increasingly participate in aspects of life that otherwise would have been forever unavailable to them.

Recently, a medical breakthrough in Italy allowed a patient who had been in a “minimally conscious state” for two years not just to regain consciousness, but to engage in conversation. The man wasn’t in exactly the same state as Sacks’ patients, who suffered from something called encephalitis lethargica, which attacks the brain and causes everything from headaches and double vision to Parkinson’s-like symptoms to catatonia or a coma-like state. An encephalitis lethargica epidemic began in 1917 and lasted over a decade, resulting in the deaths of roughly 5 million people. The patients Sacks treated contracted the disease during that epidemic and had been hospitalized and catatonic for over 30 years.

The Italian patient had been in a car accident, after which he was comatose for 40 days. He then awoke from the coma, but remained minimally conscious—he had a sleep-wake cycle, he could reach out and touch things, and he could open and close his eyes, but that was about it. When he was released from the hospital about a year after his accident, he couldn’t communicate or respond when people asked him to blink. Then his cognition took a nosedive in a way that mirrored the decline of Sacks’ patients. His movements became excruciatingly slow, and he sometimes exhibited random, almost tic-like behavior, such as clapping.

Roughly two years after his car accident, he underwent a CT scan so doctors could get a better idea of what was going on. As is typical, the doctors administered midazolam, a mild sedative often used for such procedures. What isn’t typical is the man’s response—within minutes, he began talking and interacting. He didn’t just have rudimentary conversations, either. According to the case report, the man “talked by cellphone with his aunt and congratulated his brother when he was informed of his graduation; he recognized the road leading to his home.”

This is the first time doctors have reported midazolam as promoting an “awakening” in a patient, as detailed in Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. However, the effects of the midazolam wore off after a couple hours, after which the man reverted to his previous state. Doctors wanted to confirm that the drug was indeed responsible for the dramatic shift in the man’s state, so they gave him the drug again. After just a few minutes the patient was not only responsive and talkative, but was also able to do some simple math problems. Brain scans before, during, and after the second dose of midazolam revealed that the regions of the brain affected by the drug are associated with catatonia.

Unfortunately, the long-term effects of this treatment mirror those of the patients in Sacks’ memoir. He found that his patients built up a tolerance to the drug, so he had to administer more and more of it, which resulted in side effects such as irritation, increased physical tics, spasms, and even psychosis: “For the first time, then, the patient on L-DOPA enjoys a perfection of being, an ease of movement and feeling and thought, a harmony of relation within and without. Then his happy state – his world – starts to crack, slip, break down, and crumble; he lapses from his happy state, and moves toward perversion and decay.” Eventually, the patients relapsed, and a decade after Sacks published his memoir, 17 of those patients had died, most of them from Parkinsonism. The movie Awakenings ends with Williams and De Niro once again using a Ouija Board to try and communicate.

Researchers ran up against this same problem with their Italian patient. They tried giving him another drug of the same class called lorazepam, which is generally thought to be safer than midazolam, but after a few days, the patient became agitated and angry. The doctors switched him to an epilepsy drug called carbamazepine, which apparently has allowed him to “maintain the improvement of his ability to interact and communicate with people,” though perhaps not to the same degree as he could while on the midazolam.

Still, the Italian patient’s experience, as well as other accounts of sedatives, particularly sleeping pills such as Ambien, inducing temporary consciousness in patients, gives researchers hope for treating patients in catatonic, comatose, and vegetative states. It also provides a solid lead for treating Parkinson’s, epilepsy, and other neurological disorders. And hey, it beats using a Ouija board.