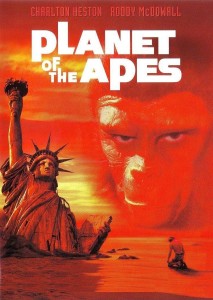

One of the reasons Planet of the Apes resonates so deeply with viewers is the plausibility of its premise. Have you ever seen monkeys up close? Their profound intelligence is clear, and there’s no question we evolved from them. Their eyes convey not just their cognitive abilities, but a deep level of awareness. Monkeys, apes, and gorillas are also emotional creatures—if you’ve ever seen Koko grieve the loss of her kitten or hang out with Robin Williams, you know they’re capable of love, sadness, and even compassion. Given their intelligence, sentience, and opposable thumbs, it’s not too difficult to imagine them ruling the world.

Planet of the Apes subeverts the paradigm that humans are the smartest and most capable life forms around. We keep primates in zoos because despite their intelligence and capabilities, we generally still believe we have the right to study them and hold them captive. I’ve seen monkeys at sub-par zoos that seem downright depressed (I even saw a monkey smoking a cigarette in a zoo once). Sure, sometimes protective measures are necessary, especially when it comes to gorilla poaching and other abhorrent practices. But to put these animals behind bars diminishes the vary qualities that fascinate and endear us—not to mention the qualities we’ve inherited from them—and much like sci-fi movies that feature robots seeking revenge for past enslavement, Planet of the Apes suggests that primates could, like robots, exceed human intelligence and even turn the tables on us by taking over. It also asks whether that would be such a bad outcome in the grand scheme of things.

Among other things, the movie challenges the morality behind keeping these animals in captivity, and it turns out that courts are deliberating the same question. In December, a criminal appeals court in Argentina ruled in favor of an orangutan named Sandra, granting her the right to life and liberty, as well as to protection against harm. Sandra was born in a German zoo in 1986 and has lived in captivity ever since, now residing at the Buenos Aires Zoo. The habeas corpus petition was filed by the Argentina’s Association of Professional Lawyers for Animal Rights, who argued that it is illegal to deny Sandra her freedom. The petition was initially denied before being granted by the appeals court.

Sandra (credit: Buenos Aires Zoo)

That ruling will lead to another legal proceeding—this time to figure out where Sandra should live. A committee will be appointed by the Argentine justice system to decide the best home for the orangutan, considering factors such as her ability to travel, her age, and available and appropriate sanctuaries.

This isn’t the first time such claims were filed, both in and out of Argentina. Similar motions have been made in Brazil and in New York State. In 2012, PETA unsuccessfully tried to apply the 13th amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits slavery and servitude, to captive orcas. The ruling in favor of Sandra would have widespread effects—first and foremost for 17 chimpanzees currently in Argentinian zoos. The ruling will also fuel a growing movement to return primates, as well as other intelligent animals such as dolphins and whales, to their natural environments, or in cases where that’s not possible, to sanctuaries. Such animals have been shown to possess “sentience, self-consciousness, and individuality,” according to University of Buenos Aires primatologist Aldo Giúdice. “We cannot be accomplices and let them suffer in prison.”

Perhaps such rulings will help build humans’ credibility and goodwill. If primates evolve to be the superior species on Earth or on some other planet we happen to land on, maybe they’ll think twice before performing brain surgery on us or putting us behind bars.