Tomorrow, I’ll be lounging in a hammock on a Thai beach drinking Mekhong whiskey, resting up for a Full Moon Party. On Wednesday, I’m scuba diving the Great Barrier Reef. On Saturday, I’ll be on Mars, peering up at Olympus Mons.

Or at least, that’s how it goes in my dreams. But what I’m talking about is better than a dream.

Given that I still don’t possess teleportation powers, the next best thing is virtual reality.

From Tron to the holodecks of Star Trek to the Matrix, science fiction has long been crazy about virtual reality. Now, science is too.

Virtual reality either recreates the existing world or creates a fantasy world into which the user can become immersed. With the help of headsets consisting of goggles–one monitor for each eye–and headphones, virtual reality programs recreate sights and sounds in 3-D. Everything you do, your avatar does.

Depending on the sophistication of the facilities, virtual reality labs might also include air nozzles and scent dispensers to enhance the sense of immersion. Sometimes, treadmills or other devices are used to create a bodily experience in virtual reality, though at this point, physical experiences such as climbing a tree or swimming don’t quite transcend realities.

Different virtual reality systems offer different ranges of interactivity, depending on speed, range, and mapping. Computer models incorporate the speed of a user’s actions and attempt to reflect them back to the user with minimal lag time, or latency. Range and mapping involve the “choose your own adventure” aspects of virtual reality–how many different outcomes your actions generate and how natural those responses are. For example, if I’m walking down a street, how fast can I go? Can I trip? Can I fall? Once I fall, can I get right back up, or can I roll around on the ground in pain? Can I sing Bob Dylan while I writhe around? A truly interactive virtual environment allows users to modify the environment, even if the modifications don’t seem logical.

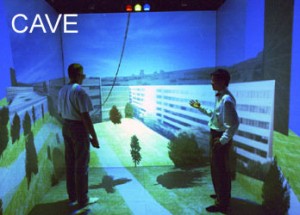

Cave Automatic Virtual Environments project images on walls, the ceiling, and the floor of a room. Instead of wearing headsets, users wear special glasses that give them a wider field of vision, and often a greater sense of immersion. More than one person can participate in a virtual CAVE experience, though programs can respond to only one set of inputs from one person; the others are observers.

Still holding out for a holodeck? Be patient. Netflix the last couple seasons of TNG–it may be a while.

Body Immersion Environments are the next frontier of virtual reality. These don’t involve goggles or avatars–these involve a computer-generated total sensory environment that the user occupies. Unlike the more conventional virtual reality environments, these would produce realistic bodily experiences–you’d actually get tired swimming or climbing a tree. Of course, BIE don’t exist just yet, as scientists haven’t mastered the conversion of energy into virtual space and then somehow animating it, or producing the illusion that one is actually there.

Another kind of futuristic virtual reality is the Brain Simulated Environment. This would involve creating an environment from within a user’s brain, rather than from an external device such as a computer. Neuroscientists believe that stimulation of specific brain cells in the cerebral cortex produces sensations such as sounds, smells, colors, etc. In other words, our sensory experiences likely don’t come from the external world—they come from our brains. If we can figure out how to evoke specific sensory experiences, there’s no end to the virtual environments we can create.

Virtual reality systems may seem like the cutting edge of gaming, but their uses extend far beyond recreation. Virtual reality can help treat patients with phobias and anxiety disorders; it is now a common treatment for PTSD and has been used successfully with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Virtual reality exposure or immersion therapy allows doctors to change the virtual environment in order to gauge the patient’s response to certain variables and triggers. Patients can enter a 3-D world in which they can see, as well as smell, hear, and touch, whatever it is that induces phobia or causes their anxiety or PTSD. Confronting these objects or scenarios repeatedly, and with the knowledge that they are at that moment completely safe, allows patients to overcome phobias and anxieties and score virtual victories that carry over into the real world.

Check out virtual Iraq, Afghanistan, and 9/11.

At New Zealand’s Auckland University, scientists are currently developing a computerized cognitive behavioral therapy technique for kids suffering from depression and anxiety. In the game, users’ avatars enter a fantasy world in which they fight negative thoughts and learn how to manage them.

If only that game had been available to Ender at Battle School!