The recent discovery of a habitable, earth-like planet has renewed buzz and speculation not only about the possibility of humans living on other worlds, but also about whom or what else is living out there.

Are there Vorlons out there somewhere? Tralfamadorians? Overlords?

Who knows? Regardless, I will cling to the hope of meeting a Tralfamadorian before I die. Or maybe after. So it goes.

What we do know for certain is that worms can live in outer space. Ender fans will immediately think of the Buggers, which appear to not be limited to Lusitania.

A study recently published in Britain’s Journal of the Royal Science Interface demonstrates that once established, worm colonies can thrive in space without anyone tending to them.

Weightlessness degrades muscles, particularly anti-gravity muscles, which counteract the force of gravity and keep joints and other body parts stable. Muscles that help us maintain upright posture, such as our abdominal/core muscles, quadriceps and glutes, and muscles that surround the spine, all weaken when in a state of weightlessness. Weightlessness also negatively impacts the heart muscle.

In addition to weakening from disuse, weightlessness also causes chemical changes to occur in muscles. Even intense exercise can’t stave off these effects; astronauts who spend extended periods of time in space don’t regain all of their muscle mass.

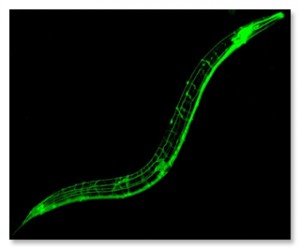

British scientists undertook the study of the effects of weightlessness and long-term spaceflight on worms, specifically the microscopic Caenorhabditis elegans. While these tiny invertebrates might not appear to have much in common with humans, they do. 2,000 of the c. elegans’ 20,000 genes affect muscle function, and scientists estimate that over half of those genes correspond to human genes.

The study began in 2006, when Discovery space shuttle’s crew included 4,000 worms reported to have come from a Bristol garbage dump. The worms spent six months living on the International Space Station before the Discovery brought the worm colony, 12 generations later, back to earth alive.

The worms lived and reproduced in liquid, rather than in soil or agar. The colony required no human tending; every month fresh food was automatically transferred to the colony. Scientists monitored the worms via camera to observe the effects of weightlessness, as well as radiation and other environmental factors.

Gravity is also essential in the development of many animals, particularly during fertilization. Uneven or improper weight distribution in eggs could lead to later deformities, among other things. While worms previously sent beyond the Van Allen radiation belt did return sterile, during this recent study neither radiation nor lack of gravity stopped or affected the reproduction of these worms.

Other studies have shown that worms can form the letter “Y” in space.

Scientists working on the study have concluded that spaceflight affects worms and humans in very similar ways. Thus, worms can be sent ahead on unmanned missions to the far reaches of the solar system and perhaps beyond, and then tested for biological effects before humans attempt the same.

If worms can live and reproduce in space long enough to reach other planets, scientists believe that humans will eventually be able to do this too.

Perhaps the Buggers are out there after all (or perhaps we’ll be the ones who put them there). Luckily, thus far there have been no reports that scientists intend on raising giant, trash-guzzling worms, but never say never. Let’s just make sure the Empire doesn’t get a hold of them first.

One Response to The Worms Crawl In, the Worms Crawl Out